Literary Scandals: Who Was the Real-Life Dracula?

My friends, let us begin drawing up some lines of conspiracy and scandal. From the outset, I am absolving myself of journalistic integrity and the usual need to provide evidence of my claims, or — more importantly in many cases — evidence that outweighs my claims. Everyone involved in this scandal is long-dead, and real, actual scholars have written about and studied this subject. In the sense of a person dedicated to finding truth, I am neither a journalist nor a scholar in this moment, but merely a literary gossip, and I dearly love a good scandal.

Let’s get something out of the way immediately: vampires — the blood-sucking, immortal, turning-into-bats, sparkling-in-the-sunlight, “I-vant-to-saaaahck-your-blooood” vampires, are not real. At least, not on our plane of reality. That I know of. And to be honest, I’d rather not know if they’re really real. But if you happen to come across one, please ask him (it’s always a “him”) why his kind seem drawn to young, impressionable women who haven’t yet formed their sense of autonomous self. On second thought, scratch that. I think I just answered my own question.

ANYWAY. We are here, denizens of the grapevine, to discuss that most infamous of literary characters: Dracula.

Any quick internet search will tell you that Bram Stoker’s character Dracula was based on Vlad Dracula, Vlad III of Romania, Vlad the Impaler. However, Stoker’s depiction of Vlad Dracula is entirely fantastical, barely based on the broad outlines of his life. It is obvious to any internet armchair historian — such as I — that someone else must have served as a much more immediate and personal reference for such an iconic villain.

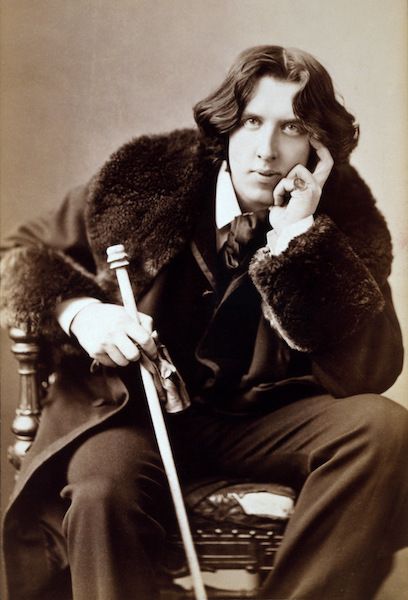

I present to you, fellow scuttlebutt enthusiasts, the one and only Oscar Fingal O’Flahertie Wills Wilde, famous author, playwright, and aesthete.

“What?” you may be thinking. “What on earth has a vampire to do with Oscar Wilde, author of The Picture of Dorian Gray and The Importance of Being Earnest?” I’m getting there. It turns out that one Abraham Stoker, Irishman, and one Oscar Wilde, also an Irishman, were part of the same circle growing up. Their parents were friends, and they were at Trinity College at the same time, where they were friends. Very close friends.

That is, until they both met Florence Balcombe, celebrated beauty. Wilde courted her first, and she accepted his suit, although the pairing was eventually broken off and Florence took the name of Mrs. Bram Stoker. Stoker’s proposal was something of a scandal in and of itself, considering that Wilde was still her foremost suitor. And, rumor has it that while Stoker was the eventual victor of the young Miss Balcombe’s heart, he never quite recovered from the discrepancy of Florence’s love for Wilde’s flamboyant, outsized dandy character. His character, in contrast, was more solid and determined, with a steady job as theater manager for Henry Irving.

In 1897, Oscar Wilde was sentenced to two years of hard labor for “gross indecency” regarding acts of sodomy, and Bram Stoker began what was to be his masterwork. In it, he describes the titular villain using the same words that the contemporary press used to describe Wilde: as an “overfed leech” and a living personification of all that is dilettante and wrong with late Victorian society.

Stoker’s revenge was entirely Pyrrhic. Journals discovered in his attic (how is it that this kind of discovery is still happening??), printed in 2012 as The Lost Journal of Bram Stoker, talk in coded language about Stoker’s own sexual preferences and predilections. What is less coded is the text of his letter to Walt Whitman:

I would like to call YOU Comrade and to talk to you as men who are not poets do not often talk. I think that at first a man would be ashamed, for a man cannot in a moment break the habit of comparative reticence that has become second nature to him; but I know I would not long be ashamed to be natural before you. You are a true man, and I would like to be one myself, and so I would be towards you as a brother and as a pupil to his master.

Bram Stoker to Walt Whitman.

This letter is printed in full, for the first time, in Something in the Blood by David J. Skal. In Victorian times, admiration for Whitman was akin to a declaration of homosexuality, almost as damning as a relationship with Oscar Wilde himself.

Stoker famously kept to himself, editing his public image ruthlessly. In contrast to Wilde, and perhaps in reaction to what he perceived to be Wilde’s recklessness regarding his sexual exploits, he retreated farther and farther into the closet, going so far as to say in 1912 that all homosexuals should be locked up — a group that definitely, in retrospect, included himself.

In the end, this literary scandal ends up being less lascivious and more a tale to tug at the heart. Two friends, rivals, lovers, and authors; Stoker put them at odds in Dracula, casting Mina as the love interest, but in the end, it is the tension between the steady, dependable Harker and the deadly, mesmerizing Dracula that compels us.

إرسال تعليق

0 تعليقات