Trouble in Romancelandia: Online Censorship of Romance and Erotica

Although the paint has dried on our posters for Banned Books Week, which took place from September 26 to October 2, the time is still ripe to talk about censorship issues, especially the online censorship that has been plaguing Romancelandia for close to a decade now.

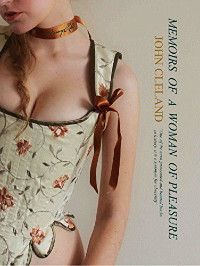

While censorship battles and romance books have had a long dance – Fanny Hill was published secretly for 200 years until the ban against the novel was lifted in the 1960s – recent changes in legislation, at least in the U.S., have added fuel to the fire.

Romance and erotica both thrive and remain vulnerable in an online space. While platforms such as NOOK, Kobo, and Amazon Kindle create avenues for self-publishing and allow authors the chance to build their own audiences instead of relying on traditional publishing houses, these same platforms have the authority to leave these books in the dark when censorship issues arise. Other than having their titles at risk of removal, authors also have difficulty publishing advertisements on Facebook and its assets, such as Instagram, because their work gets tagged as inappropriate, harmful, or otherwise not in line with content policies of these giant tech companies.

FOSTA-SESTA Laws

Back in March 2018, the Fight Online Sex Trafficking Act and the Stop Enabling Sex Traffickers Act – often cited together as the FOSTA-SESTA bills – were passed. While hailed as an active move to fight sex trafficking, these laws tampered with Section 230 of the 1996 Communications Decency Act.

Usually referred to as simply Section 230, this piece of legislation states that “No provider or user of an interactive computer service shall be treated as the publisher or speaker of any information provided by another information content provider.” In layman’s terms, websites cannot be held liable for content that users create or post. It’s important to note that Section 230 was pivotal in allowing the internet to grow. Without the assurance that companies and websites would not be held responsible for users’ behavior, we would not see the exponential growth that we have. Website creators would be taking a huge financial and legal risk every time they wanted to make a site without Section 230. Of course, there were provisions already in place to prevent criminal activity.

“Contrary to FOSTA supporters’ claims,” writes the Electronic Frontier Foundation, “Section 230 does nothing to protect platforms that break federal criminal law. In particular, if an Internet company knowingly engages in the advertising of sex trafficking, the U.S. Department of Justice can and should prosecute it.”

FOSTA-SESTA amended Section 230, creating an exception wherein website publishers would be held responsible by the U.S. government if third parties – or any users – were found to have posted ads for prostitution, including consensual sex work. The goal was to detect and stop online prostitution rings. However, other than making it harder for sex workers to advertise and increasing the risks they face in their line of work, the FOSTA-SESTA laws landed a blow to free speech on the internet.

Part of what caused this was the lack of clarity surrounding what websites should cancel and what they should allow. FOSTA-SESTA put forth a broad-based censorship model that let individual website creators and companies decide the extent of policing they wanted to do in their online space. This form of censorship targeted sex workers but soon trickled down to more general content including erotic art and authors who write romance and erotica online.

Censorship of Romance and Erotica Books

March 2018 also saw Radish – a serial fiction reading app, similar to Wattpad – banning erotica. Amazon tried to make a similar move when it removed books that fell under the erotica genre from its bestseller lists. The books were still available on the site, they could be viewed and bought, but they couldn’t celebrate their rankings. While this was fixed in a matter of days, it showed that authors could no longer count on online platforms to keep their work safe.

The FOSTA-SESTA laws, however, didn’t create erotica censorship. They exacerbated a rising trend in censorship that existed before these laws were passed. In 2013, Barnes & Noble’s NOOK began sending out notices to romance and erotica authors, saying that some of their books violated B&N’s updated content policy. The titles were removed from sale and author profiles were entirely deleted. When outrage followed, some authors gained their accounts back, but not all, and the move was never entirely revoked. Similarly, in 2012, PayPal attempted to ban erotic fiction, but soon turned tail in the face of public outcry.

The Role of Online Algorithms

While all the above cases featured instances of companies deliberately taking down books by romance and erotica writers, this form of censorship only scratches the surface of all the ways in which social media platforms undermine similar content. There have been instances when writers could not promote their books on social media because their posts and advertisements would get flagged as inappropriate, offensive, or simply not in line with the platform’s policies. As more platforms move towards automated content moderation – where algorithms, instead of their human creators, call the shots on what should be allowed online – a lot of harmless content falls through the cracks. I say harmless in a very literal sense: an ad for sex trafficking endangers the viewer’s life, while a steamy excerpt from an erotic novel does not.

We can’t blame algorithms for failing to distinguish between the two, but that isn’t to say that they’re neutral tools that need to be improved. Algorithms are trained. They follow specific patterns and grow the longer they’re put to a task. Moreover, algorithms can be biased. In 2019, two separate computational linguistics studies found that algorithms tended to flag tweets written in African American English as offensive.

“The inequalities that underpin bias already exist in society and influence who gets the opportunity to build algorithms and their databases, and for what purpose,” an article on The Conversation explains, “As such, algorithms do not intrinsically provide ways for marginalized people to escape discrimination, but they also reproduce new forms of inequality along social, racial and political lines.”

While online romance and erotica censorship is not a case of racism, it is a case of art being suppressed to suit the masses. A large population of romance and erotica writers is women. Moreover, they’re women writing about love and laying claim to their sexuality. Suppressing these voices means suppressing marginalized voices. Books, like photography, have had a history of gatekeeping.

Self-publishing used to be a great avenue to fight this issue. While traditional publishing houses are slowly becoming more aware of underrepresented voices in literature, it’s still an uphill battle. With self-publishing platforms, authors can skip the filtering process and directly give their work to their audience. It’s a neat solution, except that the very platforms that are meant to uplift writers are not doing enough to protect them from censorship.

We live in an age where we are constantly bombarded with information and entertainment, but we also live in an age where there is constant conversation around censorship and debates on what content should be policed online and what shouldn’t.

You can learn more about the FOSTA-SESTA laws, what it means for sex workers and the fight against sex trafficking, or join the conversation on censorship in Romancelandia. Or if you just want to take a break from the bleak news and delve into more romance titles, I’ve got you covered.

إرسال تعليق

0 تعليقات