Can a Translation Be Better Than the Original Book?

Can a translation of a book to be better than the original? If you’re thinking, “no, it can’t,” it might be because a translation is dependent on the original book for its very existence. A translation requires the original, but the original absolutely does not require the translation. Everything the translator does depends on what the original author did first. That author came up with the concept for the book and that author brought it to life, creating, in the case of a novel, the plot, characters, settings, etc. You might conclude that a translation is a derivative work and therefore can’t be as good as the original.

I disagree. In my opinion, the quick answer to this question is “yes, absolutely a translation can be better.” But I want to follow this conclusion with “but it’s complicated.” Let’s get into why.

Yes, a Translation Can Be Better Than the Original

I think a lot about a point I’ve heard translators make, which is that when we read translations, the translator wrote every word in that book. Every word! Yes, the original author created the book’s story and ideas. But the translator put it in language we can understand, and there is so much artistry that goes into this process. Translators are artists too.

So much changes when moving from one language to another. Translation is not simply a matter of plugging in new words to replace the old. It requires taking the original material and transforming it into a new language with entirely different structures of thought. Certain verb tenses might exist in one language but not the other, so the translator has to find a creative way to get the meaning across. Translators have to translate idioms that exist in the original but not the new language. They capture shades of meaning contained in one word in the source language that has no equivalent in the new.

Since translation requires creativity and artistry, it’s entirely possible for the translator to be a better artist than the original author. The translator might use language that is more evocative than in the original or has a better rhythm to it. They might use a broader range of vocabulary or bring forward images and resonances that were only latent in the original. They can, if they choose to, smooth over awkward places in the original or tighten up loose and sloppy writing.

Ultimately, there are so many differences between any two languages and so many decisions a translator must make, that an excellent translator can produce work that is more artful than the work they started with.

But It’s Complicated

What does it mean for one book to be “better” than another? It’s a question no two people will answer in exactly the same way. Critics have argued about this question for centuries! The same problem exists when comparing originals and translations. One person’s idea of “better” is always going to be different from another’s. So who’s to say if a translation is better than the original?

There’s so much room for differing opinions. Readers might disagree on whether a particular translation makes for a good book. Some readers may love a translation and find it beautiful and artful, while other readers find it dull or pretentious. Likewise, readers who know both languages and can compare the original and the translation might disagree on what makes a better work of art. One reader might value the awkward style in the original, for example, while the other prefers the more smoothed out version of the translation. It’s not an easy, cut-and-dry decision to make.

Whether a translator should even try to be better than the original is an open question. In the same way readers don’t always value the same kinds of writing, translators don’t always agree on how they should translate. One can argue that translators shouldn’t improve the source material. According to this idea, a translation might, arguably, be better than the original, but it’s not a good translation. It might be a better book, but that comes at a cost — the cost of not accurately giving readers the experience of the original.

Conclusions and Further Reading

At its best, a translation will be a genuine work of art, one that lives and breathes on its own. It won’t be merely a derivative of the original, but a kind of response to the original, a careful remaking of it. It has to be a remaking of the original since every word in it will be different. It’s possible that the translation will be a more artful, “better” book than the original (depending on who makes the judgment). But it’s more likely that the translation will just be different. It will capture some parts of the original brilliantly, some parts of the original will be lost, and it will add some new elements as well.

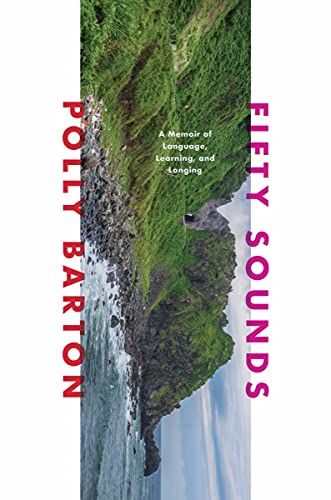

If you want to read more about translation, I recommend Kate Briggs’s This Little Art, a brilliant book about translating Roland Barthes and the nature of translation itself. Polly Barton’s book Fifty Sounds (forthcoming from Liveright on March 15) is a wonderful memoir about becoming a translator and also a study of language and the nature of translation. Finally, the article “All the Violence It May Carry On Its Back” by Gitanjali Patel and Nariman Youssef from Asymptote Journal is a fascinating, troubling look at diversity in the field of translation.

If you would like to read more about what Book Riot has to say about translation and get many great reading recommendations, check out our translation archives.

إرسال تعليق

0 تعليقات