On Slowing Down With Graphic Memoirs: Rereading The Favorites I Devoured

From my childhood speckled with comics, I remember adoring Love Is…, Garfield, Cathy, and Archie. Despite that deep, formative love, I overlooked comics in my reading for years. My reading records tell me I have finished 50 graphic novels, memoirs, and comics. Even with 50 titles floating around my brain, I still consider myself a newbie to these forms of storytelling.

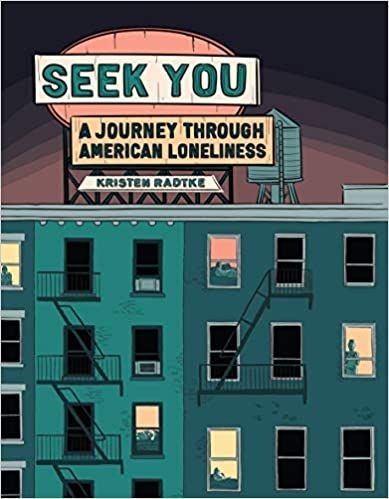

On Episode 94 of The Stacks podcast, “How We Understand Loneliness,” host Traci Thomas asks Kristen Radtke, “What do you wish more people understood about graphic books?” Radtke answers, “That they’re as serious as prose books.” The author of Seek You: A Journey Through American Loneliness continues to say, even if a reader isn’t familiar with graphic books, “they can still glean a lot from them.”

I return to graphic books late and with icebergs of regret. In my drawn-out undergraduate days, I read Gene Luen Yang’s American Born Chinese. At my bookselling job, Alison Bechdel’s Fun Home passed through my hands enough that it was cemented in my TBR list but back-burnered due to coursework. Sadly, a graphic novel or memoir would have been refreshing company between deep-reading (most of) my assigned materials twice. How I wish I could have slipped grad-school me Bechdel’s Are You My Mother? and Mariko Tamaki’s Skim, illustrated by Jillian Tamaki. To see what I glean, I revisit three graphic memoirs that moved me.

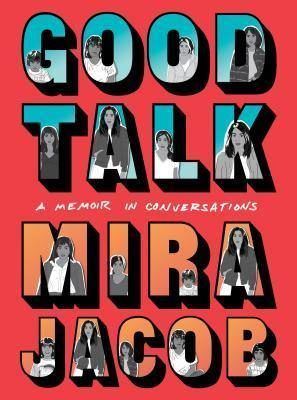

With my interest in graphic memoirs already established, Mira Jacob’s Good Talk, by feeling like a knowing hug and a lifetime of primal screams all at once, solidified my commitment to them. After turning the final page, I placed it on my partner’s TBR pile and urged, Please read it soon. When I cuddle up to revisit the title, which has graced my “want-to-reread” shelf since the birth of my “want-to-reread” shelf, my beloved says, I like that book, and we share a smile.

In an interview by Emily Raboteau for BOMB Magazine, Jacob, in addition to Pop-Up Video the VH1 television show, credits “[p]aper doll books” and “Chani Nicholas’s horoscopes,” among other things, as Good Talk’s “unexpected influences.” While rereading, I trace speech bubbles emerging from old photographs, track how and when outfits and hairstyles change. Body-jolting emotions and resonant wisdom hitch my breath in my throat like Nicholas’s popular and powerful astrological insights that I carry through my days. (If you haven’t read You Were Born for This, get on that.) I keep thinking of how Jacob writes, “We think our hearts break only from endings — the love gone, the rooms empty, the future unhappening as we stand ready to step into it — but what about how they can shatter in the face of what is possible?”

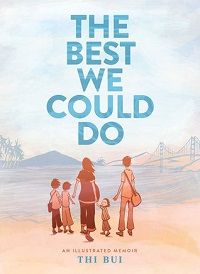

As featured on NPR’s All Things Considered, Thi Bui found inspiration in how Marjane Satrapi reflects on coming of age during Iran’s Islamic Revolution in Persepolis and how Art Spiegelman explores the Holocaust in Maus. In the interview with Mallory Yu about The Best We Could Do, Bui explains she, too, hoped to “weave the personal and the political and the historical to tell a story of the Vietnam War and all the things that caused it, in a way that I felt like I hadn’t seen before.”

Two years ago, I finished Bui’s graphic memoir, and the page depicting the author, as a child, submerged in a water-filled dream version of her apartment haunted me. Before returning the library book, I tried to memorize the image. It flutters into my brain often. That image, along with the poetic language and familial stories, pulls my finger to the hold button. At the library, the clerk tells me as I check out, You read this one already, and I say, I know. While rereading the third chapter, “Home, the Holding Pen,” echoes still me: an illustration of the father sleeping and, four pages later, the daughter sleeping. I flip back and observe how his sleeping body resembles a coast jutting out of water.

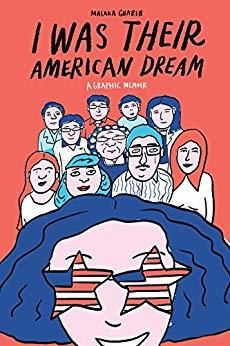

In “That’s My Story, Too: Talking with Malaka Gharib” by Michelle Ajodah via The Rumpus, Gharib, author of I Was Their American Dream, states, “The ’90s zine aesthetic really inspired me. It’s supposed to look like it’s screen-printed with halftone colors.” As you may gather from the cover, from the flag-like stars in young Malaka’s eyes, the graphic memoir has a “hot red,” white, and “electric blue” color palette. The book even includes instructions on how to create a “mini zine.”

Something about a book that begins with family introductions through dedications, photographs, and trees draws me in. Along with Gharib’s “Meet the Fam” pages, Gabriel García Márquez’s One Hundred Years of Solitude and Sarah M. Broom’s The Yellow House come to mind. While rereading, I remember that Gharib’s hilarious and tender debut gave me the spelling of words that I, Filipino on my father’s side, had walked around with my entire life, having heard them, spoken them, known them, but never seeing them written out: sabaw, tatay, nanay. Again and again, this book makes me feel seen from the rice base for every meal to a devotion to SPAM to a long, often unspoken, origin story on the tongue and more.

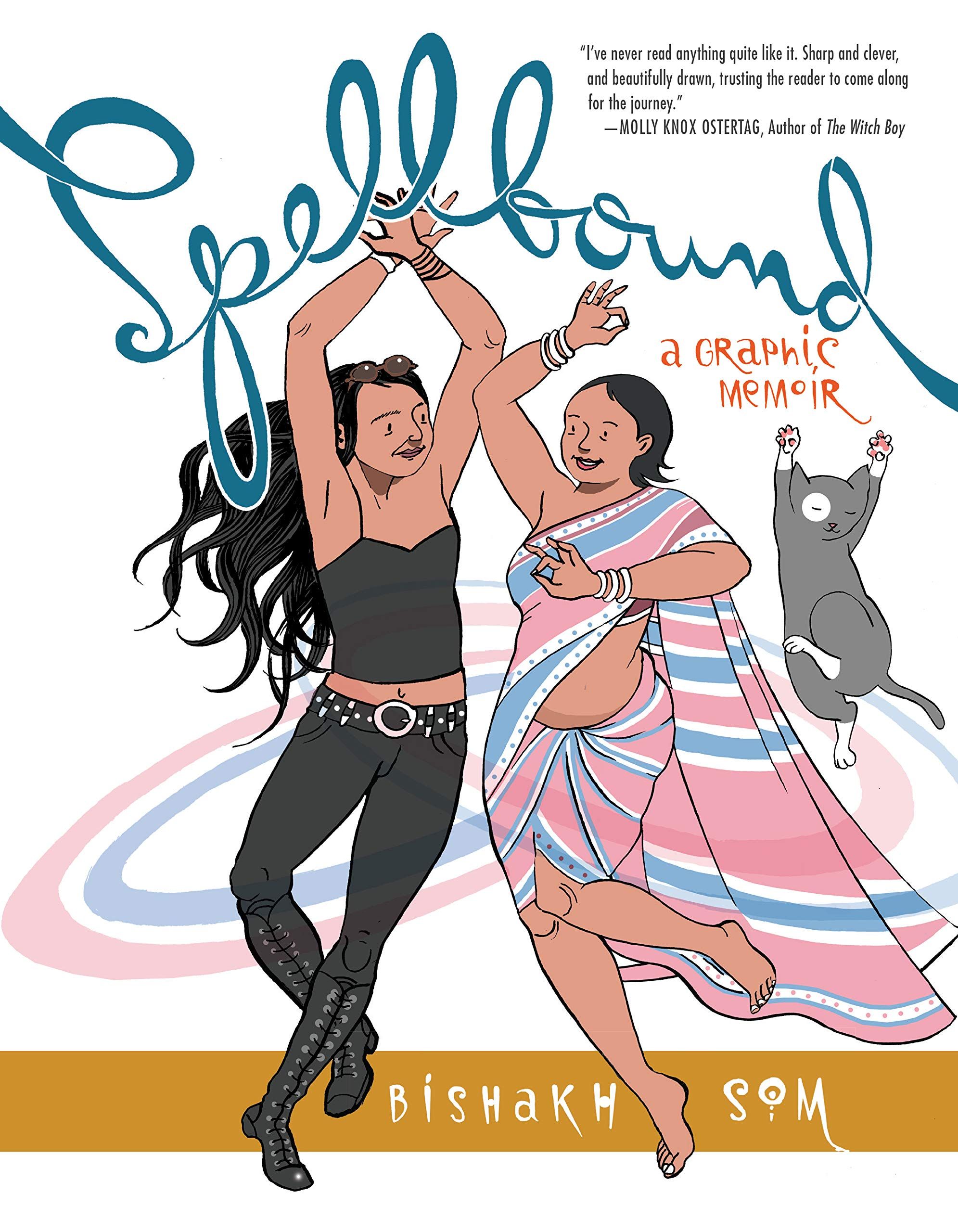

A beautiful thing about reading and rereading: one book often leads you to another. Right now, Lynda Barry’s Making Comics, which I bought after book-clubbing Cruddy with my soul sister, tops my TBR pile. Bishakh Som’s Spellbound waits in my shopping cart.

Hopefully, the same can be said about essays. If rereading and graphic fiction interest you, keep this post’s forthcoming younger sister in mind, “On Slowing Down With Graphic Novels and Stories: Rereading The Favorites I Devoured.” In the meantime, if you feel new to graphic memoirs, too, these posts helped me: “8 Graphic Memoirs By Trans Authors,” “9 Graphic Memoirs And True Stories By Women,” and “9 Sapphic Graphic Memoirs That Illustrate Lesbian And Bi Women’s Lives.”

إرسال تعليق

0 تعليقات